The Highland Scots migration from Nova Scotia to Waipu

The account of how hundreds of Highland Scots settled at Waipu, north of Auckland in New Zealand, is a stirring migration story. The community at Waipu is still proud of its Scottish heritage, which it keeps alive and is very proud of.

The grim economic circumstances in the Scottish Highlands saw an outward flow of migrants to British North America, part of what is now Canada. The first Highland Scots to emigrate to Nova Scotia — New Scotland — were nearly 200 passengers on the Hector, which arrived at Pictou in Nova Scotia in September 1773. A desire to escape grinding poverty and settle in a land of economic and land-owning opportunity in communities with their kin, saw more than 40,000 Highland Scots settle in Nova Scotia, Prince Edward Island and Cape Breton over the next eight decades.

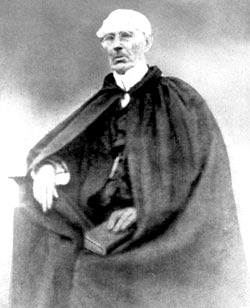

The Reverend Norman McLeod was a key figure in the migration that eventually led to Waipu. He trained for the Presbyterian ministry in Scotland but rebelled against what he saw as the lack of discipline and fervour in the Church of Scotland, so declined to enter the formal ministry. At Balchaldich in Sutherlandshire, on the west coast of the Scottish mainland, Norman McLeod (or Tormod Mór, as he was known in Gaelic) supported a group that separated from the main church. After several run-ins with church authorities Norman left Scotland in 1817 in the Frances Ann, leaving his wife and three children to join him the next year. The ship arrived in Pictou in Nova Scotia, the first step in a voyage that would end three-and-a-half decades later in New Zealand.

Pictou was already an established Highland settlement, and it wasn’t possible for Norman and those who came with him on the Frances Ann to make any kind of group settlement. Instead they were scattered about the town on the parcels of land that remained unoccupied. So when a settlement of Highlanders in the United States (in Ohio, according to tradition) invited Norman to come and be their minister, he made plans to move again. Some of his band of what were becoming known as ‘Normanites’ built a ship, derisively called the Ark by Pictou locals. In September 1819 the Ark set sail, hugging the coast around Cape Breton Island rather than taking the more direct route through the Strait of Canso and direct into the North Atlantic gales.

But when this band of adventurers reached St Ann’s harbour on Cape Breton Island, they decided this was where they would settle. They cleared land and began houses, but then returned to Pictou for the winter. The Ark was sold and each family prepared a small boat for the return voyage to St Ann’s. By spring of 1820 the group was ready to return to St Ann’s, in a fleet of seven vessels the size of modern lifeboats. After a difficult journey, during which the fleet was scattered by a storm, the travellers arrived at their new home.

More settlers came from Pictou the following year, and still more either via Pictou or direct from Scotland. Within 10 years St Ann’s was a thickly-settled community. Rev Norman McLeod gained civil authority by being appointed as a magistrate and a teacher, and had his religious authority confirmed by being ordained as a Church of Scotland minister (which he did during a visit to Ohio).

Eventually wanderlust began to stir in the Scots community on Cape Breton Island — prompted by a ruinous famine during 1848 and, the following winter, the failure of the fisheries and the promise of a better life elsewhere.

It is romantic simplicity to think of the migration that eventually finished at Waipu as a pilgrimage ‘led’ by Rev Norman McLeod. Though letters from one of the minister’s sons did attract interest in the benefits of living in Australia, contemporary correspondence by those contemplating the move doesn’t indicate that loyalty to McLeod or his form of the gospel was in any way a factor in the emigration. The McKenzie brothers, who played a leading role in the migration, were probably not even followers of McLeod.

Some time earlier one of Norman McLeod’s sons, Donald, had effectively disappeared with the brigantine Maria. He had taken the ship to Glasgow where he had been instructed to sell both the cargo and the ship, but instead of returning home he had ended up in South Australia. In 1848, after some eight years’ absence, he wrote to his father with a glowing report of life in that far-off colony. With difficult times on Cape Breton Island, a further move seemed attractive.

In 1849 Norman’s son Donald proposed a migration, or as his father said in a letter in June of that year “we have of late very satisfactory accounts from our dear son in that distant quarter; who eagerly invites his friends to the same mild and fruitful country”. Norman McLeod decided to make the move. Construction was started on the Margaret (a vessel named after the minister’s daughter). It was largely completed by the summer of 1850, but not until the following year was enough money raised to furnish it with sails and rigging.

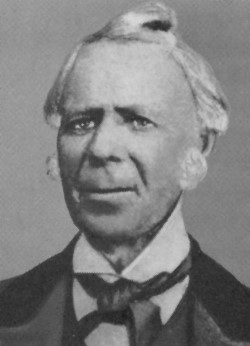

Duncan (‘The Prince’) and Murdoch (‘The Captain’) McKenzie, sons of John (‘The Smuggler’) McKenzie, commissioned the building of the brig Highland Lassie for the same purpose of emigration. These were the first two ships to make the move from Nova Scotia.

The McKenzie brothers’ ship Highland Lassie was launched on 20 September 1851. As the Highland Lassie was conducting sea trials the Margaret was being readied for departure, and she sailed for Adelaide on 28 October 1851. The Highland Lassie was set to depart from St Ann’s just two months later, but was caught in ice and forced to stay over the winter. The passengers had to disembark and either return home or stay with friends. She finally left in May 1852 and arrived in Adelaide in October of that year.

The Margaret had arrived in Adelaide just before the Highland Lassie departed from St Ann’s, in April 1852. By this time Norman McLeod’s son Donald had moved on to Melbourne. Passengers from the Margaret stayed in Adelaide for four months, during which time the ship made a return journey to Melbourne. The Margaret departed for Melbourne for the second time in August 1852 with Norman McLeod and his family and only a few of the Nova Scotians. The majority had decided to stay in Adelaide, though many of them later went on to New Zealand.

The Margaret was sold in Melbourne, as Norman McLeod thought he had reached his journey’s end. But Melbourne was not a fortunate place for the wanderers. It was in the middle of a frantic gold-rush and a typhoid outbreak claimed the lives of a number of the settlers, including three sons of Norman McLeod in the space of just a few months in late 1852.

The Highland Lassie, meanwhile, was on its way to join them. The 155 people on board were no doubt very pleased to leave after their enforced winter’s stay at Cape Breton. The ship’s complement included the owners Duncan and Murdoch McKenzie, their brother Hector and all their families, and their mother Ann McKenzie, the widow of John (‘The Smuggler’).

The ship reached Adelaide on 6 October 1852 where the passengers went ashore to begin their new lives in the southern hemisphere. Murdoch McKenzie used the Highland Lassie to trade between the Australian colonies for a while, travelling to Melbourne and Hobart before selling the vessel in late 1853.

Norman McLeod was now in Melbourne, and the Highland Lassie passengers (and some from the Margaret) were in Adelaide. Leadership of the migration moved from McLeod to the McKenzie brothers. They looked for what they wanted — enough land to establish a Gaelic-speaking settlement for their people — but nothing suitable was available. Correspondence with Governor George Grey in New Zealand showed there would be better prospects across the Tasman. New Zealand had, after all, experience with settlements of particular characteristics, whether those established by the (English) New Zealand Company, the Scots in Dunedin, or the French at Akaroa.

Captain Murdoch McKenzie took a new ship of his, the Gazelle, to Auckland with 90 folk from the Highland Lassie and 33 from the Margaret, and so it was that on Saturday 17 September 1853 the first of the Nova Scotian migrants arrived in New Zealand. The Rev Norman McLeod was not a passenger on this vessel.

After the Gazelle arrived in Auckland the migrants stayed in rented houses in Albert Street, and some of the men found work farming or building in the booming town. Murdoch McKenzie continued to use the Gazelle to trade within New Zealand and across the Tasman to the Australian colonies, and his elder brother Duncan negotiated with Governor George Grey for land. Rev Norman McLeod came to New Zealand on the Gazelle on one of those later transtasman voyages in January 1854.

It was Duncan McKenzie who had sighted the Northland coast where the group was eventually to settle, and who set out from Auckland in an open boat with a party of six men to explore the coast in detail. After visiting Waipu he decided on this area, and in December 1853 made a formal application for a block of land — this was before Rev Norman McLeod had even reached the country. Duncan’s application was soon challenged by none other than James Busby, who had been British resident when the Treaty of Waitangi was signed more than a decade earlier. Busby was ultimately unsuccessful in his protest, but this action delayed the settlers from taking up the land.

The Highland settlers finally arrived at their new home when Duncan McKenzie sailed his small schooner the Don up the Waipu river in September 1854. On board were three families, one of them his brother Hector’s, 16 people in total and all former passengers on the McKenzie brothers’ ship the Highland Lassie.

In due course news was carried back to Nova Scotia of the advantages of life at Waipu. About 900 people left for the south between 1851 and 1859 in six ships: Margaret, Highland Lassie, Gertrude, Spray, Breadalbane and Ellen Lewis. Rev Norman McLeod took up land in Waipu and remained the spiritual leader of the community until his death there on 14 March 1866.

Mathesons in the migration

There’s no completely accurate list of passengers on the six migration ships, but the best is in the recent book ‘Sailors and settlers’ by John McLean. This may still omit some of the crew, who weren’t always listed. John McLean’s book has provided these details about Mathesons in the Waipu migration.

Margaret (to Australia)

Roderick Matheson, remained in Australia.

Highland Lassie (to Australia)

Duncan Matheson stopped in Australia where he achieved some success on the goldfields. He came later to New Zealand but was killed in an accident in 1872 when working clearing bush on the Coromandel Peninsula. Buried at Waipu.

Gertrude (arrived Auckland 22 December 1856)

None.

Spray (arrived Auckland 24 June 1857)

Angus Matheson and Jessie Matheson (née Matheson) and their children Isabella and Alexander (born on the voyage). Angus was the co-owner of the Spray and a master mariner. After spending some time at Waipu the family moved a little south to Omaha, which was a better location for Angus’s shipbuilding business. The inlet where they settled is now known as Mathesons Bay.

Duncan Matheson, Angus’s brother, settled at Omaha a little before Angus and also worked there as a ship builder. Place names don’t properly have apostrophes, but perhaps this inlet is Mathesons’ Bay rather than Matheson’s Bay.

Isabella Matheson (née Cameron), Christina, Duncan. Isabella was the pipe-smoking mother of Angus and Duncan, and she arrived with her sons and her daughter Christina.

Margaret (Peg) Matheson.

Margaret Matheson, a widow, sailed with her daughters Margaret, Ann, Catherine and Johanna Matheson.

Breadalbane (arrived Auckland 21 May 1858)

Mary Matheson, a dependant of John McInnes.

Ellen Lewis (arrived Auckland 11 May 1860)

Kenneth Matheson and Flora Matheson (née McKenzie). They sailed with their married daughter Catherine (who travelled with her husband John Munro and their two daughters), and another eight of their ten children: Annabella (Annie), Arabella, Jane Elizabeth, Johanna, Kenneth, Donald Munro (Dan), Murdoch. Two daughters seem to have stayed in Nova Scotia.

Norman Matheson

Credit

This article is adapted from part of a chapter of Highland heritage: four Scottish families and their migration stories. Details of this book are here, and it is available from the author, Andrew Matheson, at PO Box 10425, Wellington 6143. Andrew, who is webmaster for the Clan Matheson Society in New Zealand, is the great-great-great-nephew of Duncan and Murdoch McKenzie, and the great-great-great-grandson of John (‘The Smuggler’) McKenzie and Ann McKenzie.

Details of Sailors and settlers by John McLeod are here.